Summary

- Lessons Learned From the Flint Water Crisis

- Is Bottled Water Safer to Drink Than Tap Water?

- Trust Polymer Solutions International

- Timeline of Flint Michigan Water Crisis

Flint Michigan’s struggle didn’t begin in 2014 when city officials discontinued using Detroit’s water system and began sourcing public water from the Flint River as a cost-saving measure. The lead-contaminated tap water crisis and the events leading up to it may have only developed in the past three years, but Flint had been a city in decline over the past four decades.

At the height of its prosperity in the 1960s, Flint had approximately 200,000 residents, 40% of which were employed by General Motors (GM). Forty years later, however, Flint’s population has been cut in half, and GM now employs fewer than 10,000 employees. According to an MSNBC report, 2013 was the first time in almost one hundred years that the city had a census population below 100,000, and all indications are that this downward trend is continuing. The 2014 population was close to 99,000, which was down from the 2013 figure of 99,791.

As decent-paying jobs left Flint, so did the businesses that had been supported by a well-paid blue-collar workforce. Since 2000, Flint has been forced to declare a state of financial emergency two times, the most recent in 2011. The decision to switch from the Detroit Water and Sewage Department (DWSD) to Karegnondi Water Authority (KWA) — a measure that was projected to save $200 million over the following 25-year period — was largely due to the monetary pressures that the financially embattled city faced.

Lessons Learned From the Flint Water Crisis

Most people take it for granted that the water that comes from their faucet is safe to drink. They trust the government to employ the safeguards that have been put into place to ensure that they aren’t slowly poisoning themselves. Unfortunately, in the case of Flint residents, their trust in tap water regulations was met with drinking water that, in some cases, had hundreds of times more lead in it than federal law allows.

Like most crises, the situation has its share of heroes. Without the efforts of Lee-Anne Walters, Miguel Del Toral, Dr. Marc Edwards, Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, and several other key individuals, the Flint Michigan water crisis may have continued indefinitely as the damage that the chlorine additive had caused to the pipes couldn’t have been undone by switching water sources.

Once the water crisis came to light, however, bottled water companies immediately began to deliver free pallets and racks of bottled water to critical areas within the city of Flint — even before a federal judge mandated that the city start providing it. This philanthropy has been instrumental in ending the residents’ exposure to the existing hazard. To date, members of the International Bottled Water Association (IBWA) have donated the equivalent of more than three million half-liter bottles of water to Flint residents.

Is Bottled Water Safer to Drink Than Tap Water?

Anyone who drinks tap water needs to know whether it’s safe. EPA tap water rules for lead have been in place for years, but in the events leading up to the Flint Michigan water crisis, (See Timeline Below) those regulations were ignored. When comparing bottled water vs. tap water regulations, it’s important to recognize that bottled water is a food product that is comprehensively regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Here are some of the FDA’s standards for bottled water:

- The FDA standards for bottled water are required by law to be as protective of the public health as the regulations issued by EPA for tap water. However, in some instances – such as lead – the FDA bottled water standard is more stringent than the EPA tap regulations.

- The type of bottled water must be identified on the label using the following categories that are set forth in the FDA standards of identity: artesian, deionized, distilled, drinking, groundwater, mineral, purified, sparkling, spring, and well water.

- The FDA Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition oversees bottled water regulation. Bottled water is also subject to state regulation.

In addition to FDA standards, bottler members of IBWA must also comply with a Code of Practice that includes stringent rules that often exceed government requirements. In addition, all IBWA bottler members must undergo an annual inspection by an independent third-party organization to demonstrate that they meet all FDA and IBWA requirements

Trust Polymer Solutions International

At Polymer Solutions International, we manufacture and sell water racks and pallets made from hygienic and durable plastic for heavy use. Plastic isn’t porous, so our products aren’t as susceptible to bacterial contagions as pallets or racks made from organic materials, like cardboard and wood. Our products can be washed and disinfected for repeated use.

Polymer Solutions International is a global leader in the bottled water transportation industry, and our ProStack bottled water racks are used by nearly every major bottler. We are proud of our business partners who participated with us in assisting the residents of Flint during their time of need, and we will continue to be there until the crisis ends.

A Timeline of the Flint Michigan Water Crisis

To better understand the crisis that ensued, it’s worth taking a poignant look at a timeline of events:

- June 2012 to April 2013 – City government officials seek cheaper ways to supply water to residents. By connecting a pipeline to KWA, they estimate annual average savings at $4 million.

- April 16, 2014 – Flint Emergency Manager Ed Kurtz announces that the city will switch from DWSD to KWA. Because KWA doesn’t have a pipeline to Flint, water will be sourced from the Flint River until KWA water comes online in 2016.

- April 25, 2014 – The city begins drawing water from the Flint River. In a press release intended to assuage the concerns of residents over the safety of the water, Mayor Dayne Walling says, “It’s regular, good, pure drinking water, and it’s right in our backyard. This is the first step in the right direction for Flint, and we take this monumental step forward in controlling the future of our community’s most precious resource.”

- May 2014 – Residents begin to complain about the odor and color of the water despite assurances from Utilities Director Daughtery Johnson, who stated that the water would be harder than the DWSD water to which they were accustomed, but the Flint residents wouldn’t notice a difference.

- August 2014 – A boil-water advisory is issued as E. coli and total coliform bacteria are detected during water testing. This lasts through September. Flint increases the chlorine levels in the water to counter the threat of pathogens.

- October 13, 2014 – After observing the corrosive effect that Flint River water is having on their engine blocks — presumably due to the increased chlorine levels — General Motors announces that it won’t use Flint public water at its local plant.

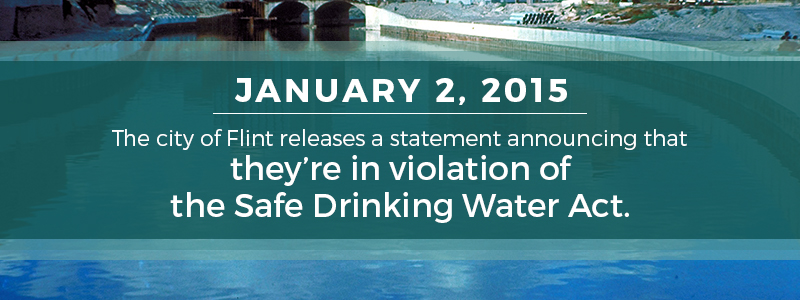

- January 2, 2015 – The city of Flint releases a statement announcing that they are in violation of the Safe Drinking Water Act due to an increased level of trihalomethanes (TTHM), which can result from chlorine interacting with organic matter. The Center for Disease Control considers some TTHMs carcinogenic. The document assures residents that this is not an emergency. It further states that unless residents have someone in their homes who is an infant, an older adult or someone with a weakened immune system, they will not have to take any additional precautions.

- February 18, 2015 – Lee-Anne Walter, a Flint resident, complained of brown water coming from her tap and claims that her children are developing rashes and that one of her son’s physical growth appears to be inhibited. A test of Flint’s public water in her home shows high lead content. The test reveals the water at 104 ppb (parts per billion). This violates the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Lead and Copper Rule, which requires drinking water systems to not only test water at the plant but also to test samples from consumers’ taps. Lead concentrations must be below 15 ppb and copper concentrations must remain below 1.3 ppm. If more than 10% of the samples taken from taps show higher levels of either, the water provider must implement control corrosion measures.

- February 2015 – An EPA water treatment expert Miguel A. Del Toral expresses concerns about the way the state of Michigan’s Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) severely underestimated the lead contamination of the water because they were flushing the system before compliance testing.

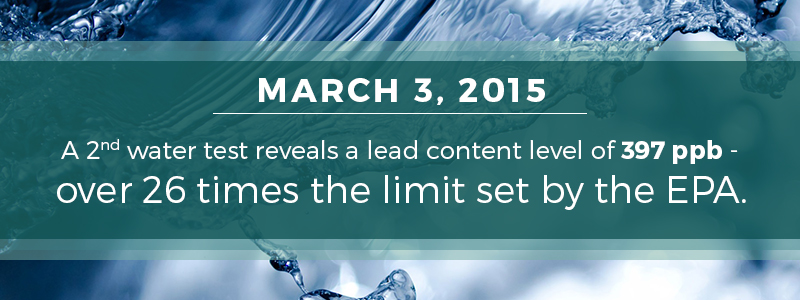

- March 3, 2015 – A second water test in the home of Lee-Anne Walters reveals a lead content level of 397 ppb — over 26 times the limit set by the EPA.

- March 12, 2015 – Veolia, a consulting group hired by Flint to conduct an independent study, releases a report addressing the TTHM levels and makes recommendations to improve the quality of tap water. The report claims that the water was in compliance with both the state of Michigan’s and the EPA’s requirements, and therefore, is safe for drinking. Lead or lead levels are not mentioned anywhere in the report.

- April 24, 2015 – According to an EPA Emergency Administrative Order, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality had informed the EPA that the Flint Water Treatment Plant hadn’t implemented corrosion control measures. This is particularly significant because investigators later blame pipe corrosion for the increased lead levels in Flint’s drinking water.

- June 24, 2015 – An internal memo drafted by Miguel Del Toral is sent to Thomas Poy, Chief of the Ground Water and Drinking Water Branch of the EPA ahead of a full report. The memo expresses Del Toral’s concerns about the quality of the water in Flint. Del Toral mentions that the practice of pre-flushing the pipes prior to testing the water would likely lead to improper readings. The memo discusses Lee-Ann Walters’ water and lists the lead-level ranges from her drinking water sample at 200-13,200 ppm.

- July 15, 2015 – Del Toral’s memo was leaked by the American Civil Liberty Union to Michigan Radio. Brad Wurfel of the MDEQ assures Flint residents that the water is safe.

- August 20, 2015 – Michigan Radio reports that the ACLU of Michigan is claiming that two critical lead test samples were left out of a report to ensure that the sample collection’s average remained under the maximum amount of 15 ppb allowed under the Lead and Copper Rule. The ACLU report is no longer available but has been preserved and quoted by Michigan Radio, and the report found: “that the city, operating under the oversight of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, took multiple actions that skewed the outcome of its tests to produce favorable results.”

- August – September 2015 – A Virginia Tech research team under the direction of water treatment expert Dr. Marc Edwards conducts an independent study of tap water at Flint residences. In September, they publish their findings on their website. They deem 269 of the 277 kits to be valid samples. The results indicate that the ninetieth percentile of the Flint samples have a lead count of 25 ppb and that several individual samples had a lead count of over 100 ppb. One particularly concerning sample had a lead count of over 1,000 ppb after the pipes leading into that home had been flushed for 45 seconds. The Lead and Copper Rule requires the water supplier to undertake anti-corrosion measures if more than 10% of the samples have a lead count higher than 15 ppb. The sample results indicate that Flint far exceeds that level.

- September 24, 2015 – Pediatrician Mona Hanna-Attisha reports increased blood lead levels among children 5 years of age living in Flint after the switch to Flint River water.

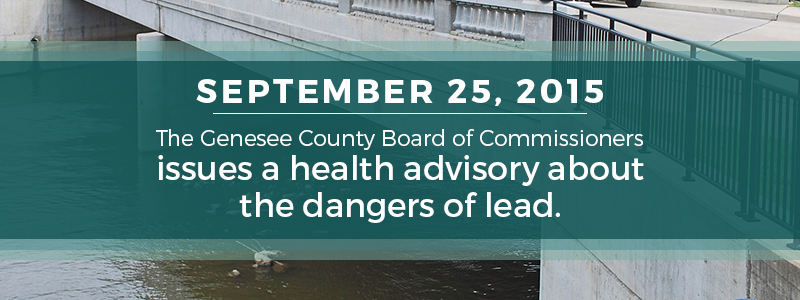

- September 25, 2015 – The Genesee County Board of Commissioners issues a health advisory about the dangers of lead. The advisory informs readers that there is no safe level of lead in the human body, but the greatest dangers are to children under 5 years of age and pregnant women.

- October 1, 2015 – City officials warn Flint residents to stop drinking tap water due to high lead levels.

- October 2, 2015 – Governor Rick Snyder releases a comprehensive action plan for the Flint water crisis. The main points of the plan include automatic testing in Flint public schools to ensure the safety of the drinking water, free testing for non-public schools, free water testing to Flint residents, free water filters for Flint residents, increased health exposure testing, corrosion controls for the Flint water system, replacement of lead service lines, expediting the completion of the KWA water pipeline, adding an EPA expert to the Safe Drinking Water Technical Advisory Committee, and enhancing a lead education program for Flint residents.

- October 16, 2015 – Flint switches back to their previous Detroit water supplier, which is now called Great Lakes Water Authority. Governor Snyder sites Lake Huron as being a more stable source, corrosion controls and resident confidence in this utility provider as the reasons for the switch.

- October 18, 2015 – MDEQ Director Dan Wyant sends an email to Detroit News suggesting that the lack of proper corrosion controls was due to a misunderstanding about the Lead and Copper Rule for communities with over 50,000 residents. Wyant explains that because it’s unusual for larger communities to switch their water sources, the way that Flint did, the MDEQ staff lacked the experience for the larger Flint water switch.

- November 9, 2015 – Karen Weaver assumes the role of mayor after defeating incumbent Mayor Dayne Walling, who had been in office since 2009.

- December 9, 2015 – In an attempt to stem the corrosion in the water transmission pipelines and restore their protective coating, Utilities Administrator Mike Glasgow advises the Flint city council that his department has boosted phosphate levels in the city water system and that the difference shouldn’t be noticeable to residents.

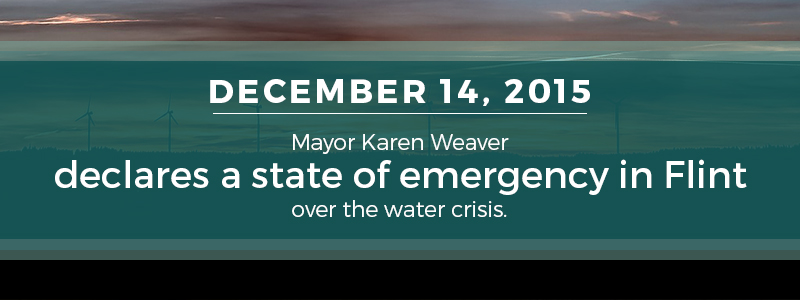

- December 14, 2015 – Mayor Karen Weaver declares a state of emergency in Flint over the water crisis.

- December 28, 2016 – In a preliminary report sent to Governor Snyder, the Flint Water Advisory Task Force places the primary blame for the water crisis on the MDEQ: “We believe the primary responsibility for what happened in Flint rests with the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ). Although many individuals and entities at state and local levels contributed to creating and prolonging the problem, MDEQ is the government agency that has a responsibility to ensure safe drinking water in Michigan.” Governor Snyder also vows to hold the parties responsible for the water crisis accountable for their failure. The report triggers the resignation of Dan Wyant and spokesperson Brad Wurfel of the MDEQ on the following day.

- January 5, 2016 – Governor Snyder declares a state of emergency for Genesee County where Flint is located.

- January 12, 2016 – In response to the Flint, Michigan water crisis, bottled water is distributed by Michigan National Guard troops.

- January 16, 2016 – President Obama declares a state of emergency for Flint, which allows FEMA to provide equipment and resources to the city.

- January 21, 2016 – The EPA issues an Emergency Administrative Order stating that the measures taken by the city of Flint and the state of Michigan were inadequate to ensure the safety of the water.

- February 3, 2016 – Flint officials testify in front of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform.

- February 16, 2016 – Governor Snyder testifies in front of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. He indicates that the Flint Michigan water crisis a failure of government at the local, state and federal level.

- March 2016 – The International Bottled Water Association (IBWA) announces plans for partners “Nestle Waters North America, Walmart, Coke, and Pepsi to provide up to 6.5 million bottles of water to approximately 10,000 Flint public school students through the end of 2016.” This is part of an ongoing effort by bottled water manufacturers and supporting industries to alleviate the crisis.

- April 2016 – A new report from Dr. Edwards’ Virginia Tech group advised that the lead levels in Flint’s city water is improving, but still not safe to drink. This is based on data that the research team gathered via sample testing during the month of March.

- April 20, 2016 – Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette announces that three state officials will be charged criminally over tampering with the results of lead tests: Stephen Busch (MDEQ), Michael Prysby (MDEQ) and Michael Glasgow (City of Flint).

- June 22, 2016 – Schuette announces that he intends to file a civil suit against two corporations. One is Veolia, the company that prepared the previous year’s report that neglected to mention lead levels. The other is Texas-based Lockwood, Anderson & Newman, which is a company that helped run the water treatment plant that drew from the Flint River. Both are accused of negligence, but the suit also names Veolia for fraud.

- July 20, 2016 – Schuette criminally charges six more individuals. Three are from the MDEQ and the other three worked for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. The latter are accused of not releasing a report that showed unsafe lead levels in Flint children.

- August 2016 – Michigan summer water testing shows that Flint’s water meets federal guidelines in some, but not all areas.

- November 2016 – An estimated three million bottles of water have been delivered to Flint Michigan residents since the beginning of the crisis. Organizations like Convoy of Hope, International Bottled Water Association (IBWA) and its member water bottlers continue to donate free water to the city’s residents.

- November 11, 2016 – U.S. District Federal Judge David Lawson orders the state and city to provide four cases of water per week to every resident until it can be determined that the household in which that person resides has a lead filter.